This month is a little diferent we have a featured artist, who happens to have a show on at the minute so we asked a photographer who went to see the show to give us thier take on this work.

THE ARTIST - RICHARD KENTON WEBB

BIO -

Richard Kenton Webb MA (RCA)

Richard Kenton Webb (b.1959) is a British artist and educator. He is one of the few British artists trained at both the Slade and at the Royal College of Art, studying under and alongside many well-known artists. He carries these conversations in his DNA.

Webb has taught at many top art colleges in the UK. Having lived in Gloucestershire for 35 years, he moved to Plymouth in 2020 to join the team at Arts University Plymouth as Subject Leader for BA (Hons) and MA in Painting, Drawing, and Printmaking.

Webb has been awarded several prizes and residencies. In 2016, he was shortlisted for the John Moores Painting Prize and in 2020, awarded first prize at The London Sunny Art Prize. Then, in 2022, he was invited to the prestigious Josef and Anni Albers Foundation Residency in Connecticut USA. Whilst in America, he embarked on a suite of 72 drawings for his Manifesto of Painting.

In 2021, Webb completed 10 years of work dedicated to a Conversation with Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost -128 drawings, 40 paintings and 12 relief prints. This led to a commission of 12 drawings in response to Milton’s poem, Lycidas, for the Milton Society of America; a chapter in The Synergies of Drawing and Painting Paradise Lost, Milton Across Borders and Media, OUP (2023); and a solo show at Milton’s Cottage in Chalfont St Giles to mark 350 years since Milton’s death. Webb’s work links colour and narrative, fusing his drive to share, teach and inform.

Webb exhibits internationally and has works in private collections around the world. He is represented by Benjamin Rhodes Arts, London where he recently had solo and two-man shows.

1 - Could you explain your practice? Only you know why you do what you do.

I can summarise my practice in three words: colour, hope, and wonder.

For me, this is a way of life. My life’s vision is to communicate the practice of colour. Colour is paint. This is an immersive, embodied experience, so I make all my own paints from pure pigments. Since the early 1990s, when I posed the question ‘is colour a language?’ whilst teaching at the Slade School of Fine Art, I have been involved in a personal pilgrimage into colour. To know colour is to probe the heart of the human condition. From 2000 to 2005, I went on to create 22 diptychs representing a Colour Grammar; then, 22 sculptures as Colour Forms; and from 2007 onwards, explorations into Red and Orange, then a Warm / Cold Contrast, Yellow, and then a Light / Dark Contrast (my Conversation with Milton’s Paradise Lost). The colour Green has been my subject since arriving in Plymouth, culminating in my thesis A Manifesto of Painting. I am looking forward to exploring Blue and Violet very soon.

2 - Is art relevant today?

We are living through dark times. Artists of every discipline have the power to comment and bring hope to desperate situations. We can make very important images that affect society. On a personal level, I have been able to expose the bullying, prejudice, and injustice that I experienced in academia. These same paintings and drawings have given hope to others who face similar issues. So, although the work is intimate and personal, it can also be relevant on a universal level.

The artist often feels like an outsider, sitting on the fence, commentating, reflecting, and communicating the invisible. We seem to have one foot in the community and the other out of it. The government asks us ‘What can you give back economically’, but artists should be allowed to think freely.

Over the last fifteen years, I’ve seen a re-emergence of painting around the world, with the potential to expand across many fine art disciplines.

I believe that painting is a human language that will never disappear. For centuries, the artist’s imagination and the alchemy of materials have fused to create truly remarkable paintings. Words can fail us, but by engaging with materials, an artist can transfer their inner world into a composition. The materials and our imaginations can unite into visual poetry, communicating a hidden realm.

Painting is a language outside of words and has the power to speak directly to the heart, crossing disciplines and borders. It is counterculture, a refreshing non-electrical activity, and can be, simply, mud on canvas. This is at odds with our instantaneous culture. Against a backdrop of the digital, I envision a counterculture where we can engage slowly and therapeutically with the physicality of paint.

This is why painting will always be relevant.

3 – We are always asked what other artists influence us, we want to know what art you don’t like and which influences you.

Paul Gauguin once said, ‘There are only two kinds of artists – revolutionaries and plagiarists.’ This summarises what I like and don’t like.

There are a lot of counterfeits who call themselves ‘artists’ and yet, have no practice. In other words, they talk the talk, but they don’t walk the walk. For me, being an artist is a way of life. There are no shortcuts. You lose your integrity when you take shortcuts. As an educator, I’ve learned to be open about things I don’t like. I tell my students to be open about what they’re looking at, even if it’s work they don’t like. This could teach them something new about themselves and their responses.

I do encounter a lot of superficial work that tries to talk about deep things and yet seems very shallow. This is what Sister Wendy Beckett calls ‘one-look art’. It may claim to be important, but it’s vacuous. When I stand in the presence of the work, I need to be convinced that there’s passion and belief behind it. I can then respect the work because it has integrity and honesty.

I am constantly reading and dipping in and out of books, especially art books. Most recently, I’ve been reading Shakespeare’s last play, The Tempest and T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets. I’m also bothered by William Blake’s drawings for Milton’s two poems, L’Allegro and Il Penseroso because they’re such a surprise. I grab any opportunity to jump on the train to St Ives to see Barbara Hepworth’s Conversations with Magic Stones. This puts me in the right frame of mind to understand the primitive qualities of the ocean and the great moors of the West Country. So, my inspiration comes from so many sources, but mainly poetry, literature, plays, music, painting, sculpture, but also philosophy. I’m talking about triggers that shift my imagination, like being in the landscape where I see and hear something new.

4- If you could go back 10-20 years what would you tell your younger self?

I didn’t understand the darkness I was facing in the early 2000s. Suddenly, there was a great deal of intolerance towards Christianity and painting, especially in academia. My advice is to blow the whistle if you feel bullied. Be confident. Speak out and point out injustice and prejudice, but only if you feel strong enough. There should be space for every belief and artistic discipline – everyone must feel free to express themselves without fear.

5 – If you could go forward 10-20 years what do you hope to have done or not done?

I hope that I will be alive to complete my lifelong quest into colour, complete Blue and Violet, and reflect and share the wisdom gained from my pilgrimage into colour. I also hope that I will have kept my integrity to my last breath.

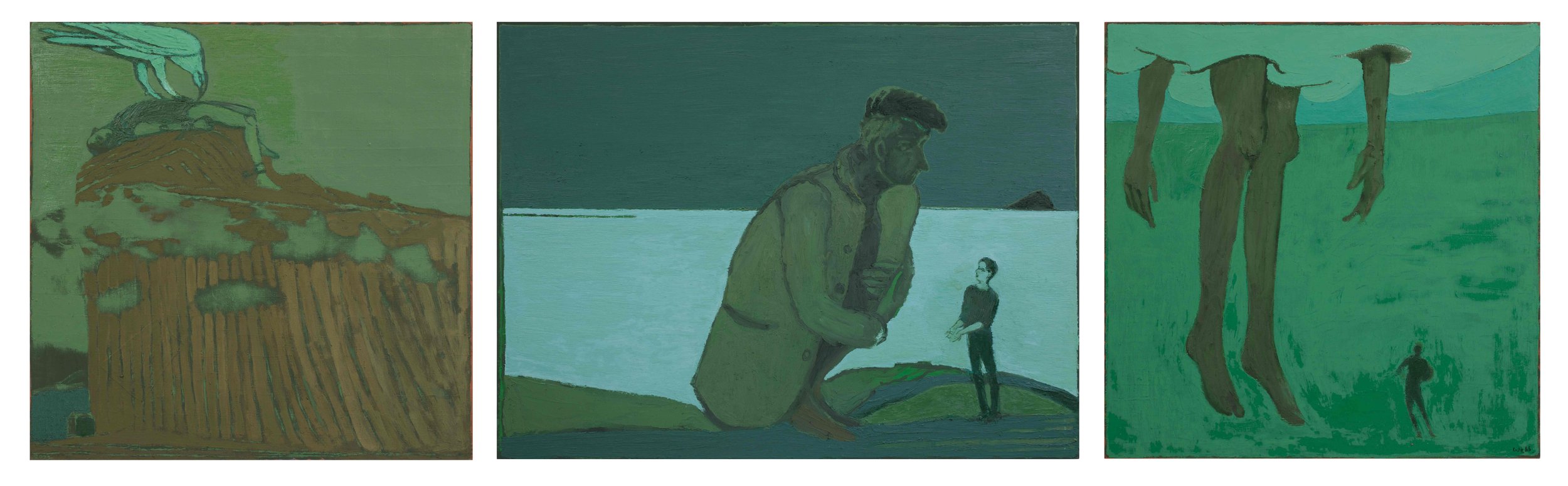

The Waste Land, Triptych, oil pigment on cotton, 68 x 273cm, 2023

web site - www.richardkentonwebb.art

Instagram - @richardkentonwebb

MILTON’S COTTAGE - REVIEW AND GALLERY BY JUSTIN PIPERGER

My brother-in-law grew up in Chalfont St Giles, and I would come to nearby Denham over the lockdown years to photograph the archives of the great Sanderson wallpaper empire. It’s just a few miles on from there to here where I’ve come to photograph the charcoal works of Richard Webb on the walls of Milton’s Cottage.

Milton, blind Milton, came here to escape the ravages of plague-ridden London and I think of the lateral flow tests I was forced to undertake each time I visited Denham from the black clouded city, the plague of our times.

I love Blake’s drawings of Milton’s epic poem, and brought John Carey’s essential Paradise Lost on our Catalan holiday some years ago, the pages and my mind wilting in the southern heat and so was thrilled to regain the thread once more in this place.

The pictures hang on porridge-like wattle and daub walls, by milk churns and stained glass, and among the darkened furniture and honeyed paintings. At each threshold, I bang my head on the low doorways and wonder if a fluency of Latin or mandolin will ensue.

In pitch-blackened inglenooks I search for light sockets and the wonderful Kelly, keeper of the house, helps source the switches for picture lights and candelabra which lie in weird places, wires coiling like snakes through this pre-electrified place.

The Devil’s work.

In corridors sunshine streams through the half door, heady purple flowers reflecting on the glass of Richard’s pictures and I fight with polarisers to cut out this glorious, blazing paradise without.

When the volunteers arrive they eye me with due suspicion and I hurry my way through the warrens of rooms before opening time.

I hear Kelly describe Richard’s work in a soft babble somewhere afar; a French waiter tempting his customer to a comely pudding, as Satan tempted Jesus atop the mount

“Tibidabo!” as the Devil says to Christ-

I shall give you

In the sun kissed garden I sit at the far end, in the covered seat eating a London sandwich among the fatted bees and birdsong.

I think of Richard’s drawing of full bosomed Delilah astride her shackled prey and cannot avoid the strains of Tom Jones drifting through

Why oh why Delilah?

I think of Samson’s long hair and remember, perhaps wrongly, that he too was blinded

And I think of my good friend Gideon, also a long-maned hunk, who has recently been seduced by a fetishist who dresses him in rubber for nights at the Torture Garden.

Good and evil

Gardens

Where are we now?

Tempted by a cigarette, I hide in the shadows away from judging eyes.

On the way back home and passing again the public toilets of Chalfont St Giles I think of my brother-in-Law, realising then he shares his name, Michael, with the great Archangel, and I press play on John Leonard’s audiobook of Paradise Lost looking forward to hearing what part he had in the saving of Mankind.

The road stretches out to the M40 and so back to Pandemonium I make my solitary way.

Justin Piperger 2024