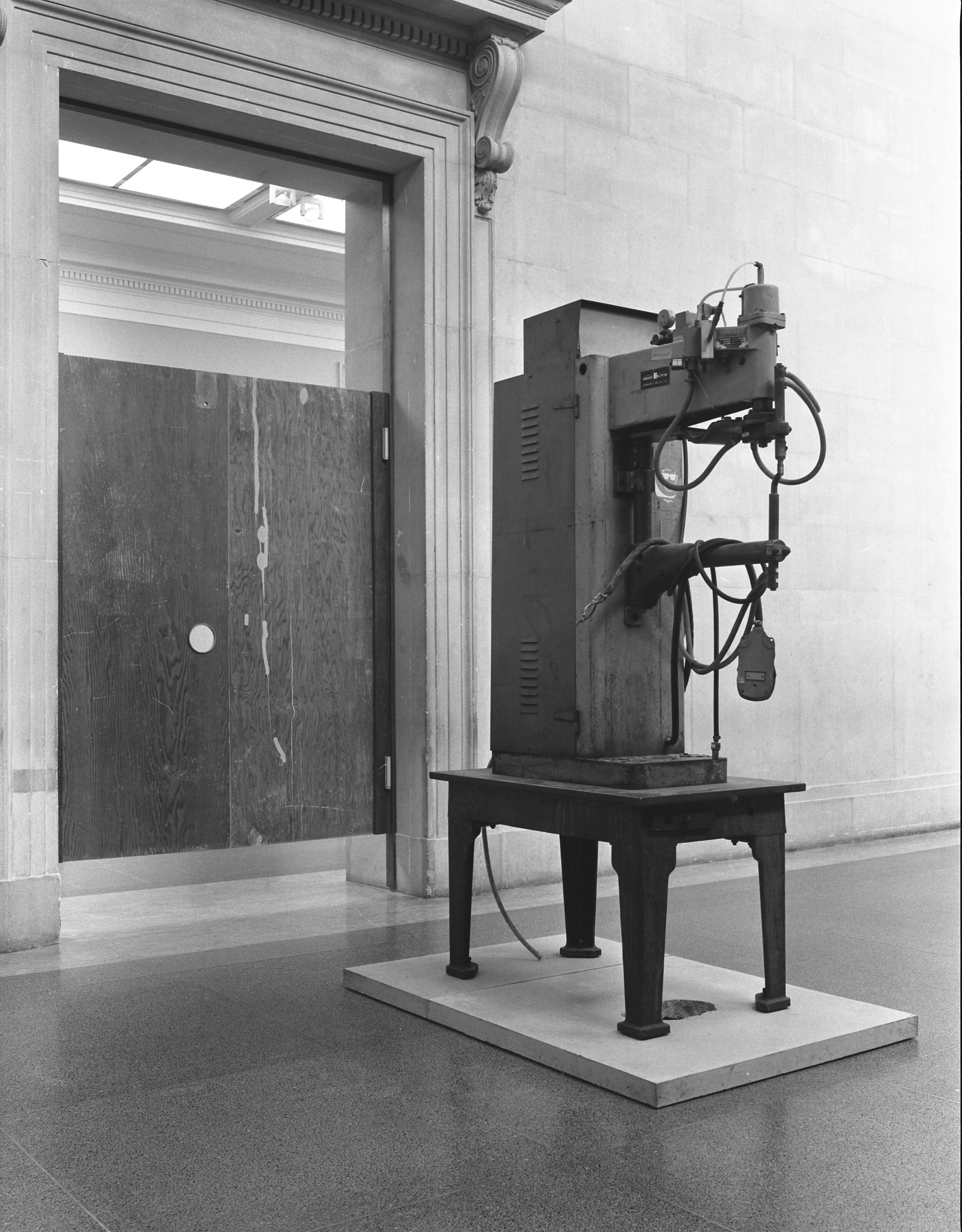

Mike Nelson is best known for his large-scale installations, in which visitors move through immersive spaces of his invention, His work is suggestive, uncanny, poetic, experiential, sculptural realism, that sits between reality and fiction. His tableaux are places of experience, tactile and immersive with the audience becoming part of the piece as they walk through, a broken narrative. Using found matter and objects, Mike’s work is intensive; with a level of detail that is exceptional, and what gives the work a sense of intrigue. An artist you do not want to miss.

Biography

Born in Loughborough (UK) in 1967, Mike Nelson lives and works in London. His work has centred on the transformation of narrative structure to spatial structure, and on the objects placed within them, immersing the viewer and agitating their perception of these environments. The narratives employed by the artist are not teleological, but multi-layered, and often fractured to the extent that they could be described as a semblance of ‘atmospheres’, put together to give a sense of meaning. The more discrete sculptural works are informed by this practice, often relying on their ambiguity to fade in and out of focus, as a sculpture or thing of meaning, and back to the very objects or material from which they are made. By working in this way the more overtly political aspects of the early works have become less didactic, allowing for an ambiguity of meaning, both in the way that they are experienced and understood. This has led to the possibility of the viewer being coerced into a state where the understanding of the varied structures of their existence, both conscious and sub-conscious, are made tangible. Nelson represented Britain at the Venice Biennale in 2011 and has twice been nominated for the Turner Prize (2001 & 2007).

• How do your ideas start, and consequently progress into actual works, what is the process you use, or work through to get to a finished piece?

The thinking process in regard to ideas has developed with time and has become cumulative - in many ways work has become easier in that the work has become more embedded by the simple passing of time and the things done within that period. Making work as a student was difficult, your life experience, reflections upon it, and the limited history of your own art all conspiring to de-rail your attempts. As time moved on I found I shifted from a didactic, ideas-led approach that used the structures of conceptualism to shore itself up, to a more narrative-driven arena of ideas. In this arena, I could still have the freedom to play and create whilst still communicating a message but through more ways than purely the theoretical; using the senses to evoke empathy perhaps. The idea is the structure, sometimes a physical structure. However, the communication is prose that is written within the space with the idea – both mental and sometimes physical – constantly feeding the process. It’s more a process of knowing what you want to communicate than how.

• How do you manage the logistical nightmare of gathering, storing and dismantle such big installations – The Asset Strippers, my operational head was going crazy considering what a huge task this must have been?

I have built many huge works with thousands of component parts and pretty much all of them have been sourced by myself over the years. The Asset Strippers marked a shift in that process in that it was mainly ascertained online through liquidation auctions by myself and my friend Paul Carter - this was pertinent to the meaning of the work but it also reflected the shift of how things are acquired online now. Prior to this, all was bought in salvage yards, demolition merchants and flea markets around the world. Work like I, IMPOSTOR at the Venice Biennale was constructed from material sourced in Istanbul, Italy and the UK; every object, timber, door, window etc I found and orchestrated. Again, it’s a cumulative process; if I had to find every element for a work like this before I started building it wouldn’t work in the same way, but given the long timeframe of the build it was possible to be searching and adding as I constructed. A work like A Psychic Vacuum in New York in 2007 worked in a similar way. Dismantling I try to avoid!

• You have said that much of your work is dismantled and not kept and it is the temporality that is so exciting - but do you think this may change as the items are beautiful as sculptural objects?

Certainly, my position in regard to this is changing, as I change and age. Temporality is a lot more graspable and romantic when it is abstract when you are young, but as mortality seeps into your consciousness its appeal and reach can dwindle. That said, I still would prefer to be remembered by a legend or myth – no matter how absurd – than by an object.

• Do you think your work will change as life has become so IT-centric - how does the physical and the virtual sit with you?

I’m not sure. As you may imagine, I am pretty analogue. Just as The Asset Strippers could be seen as a fitting elegy for Britain at the time of Brexit, a final goodbye to the Empire, to what paid for it – industry – and to materiality itself, you could also see it as an elegy to myself, to all the things I am, or could be seen to represent. I may remain as a curiosity if the acceleration of change continues in the same direction, or I may be discarded, like the litter from a roadside picnic – which could also give me some wry pleasure.

• In the past you have said you were influenced by Paul Thek, who since then has influenced your work, or who have you come across more recently that makes you think?

I still teach a bit, both at Kingston University London and at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam, and I would say that it is the artists and students I have met at these institutions that have made me think. Sometimes it is because they are making great art but more often it is because they are travelling from a land that I have not been to and cannot visit. They are a portal into an understanding of the same world but at another point of comprehension.

• I see your work as Tableaux, do you think this is a style that isn’t talked about enough as opposed to installation, I personally feel they get mixed up in translation, what’s you’re thinking on this?

I like very much the word tableaux and would favour it over installation. The works of Kienholz I would always describe like that, and the films of Parajanov – which is a construction of tableaux. A semblance of atmospheres could be another way to describe them, this is how Lovecraft spoke of his own writing. Ultimately these are all just labels, but if I was to be ascribed to a lineage of artists those that could be said to be represented by this word would not be a bad one!

• The Uncanny is the theme of this next Issue, your work does have the feeling of the Uncanny, is this intentional?

No, I am drawn to the uncanny but to render something so you cannot be intentional.

• Can you tell us about new work that you are developing?

I’m developing a large work for a building in Italy that will attempt to reflect upon the political history of the region, its shift to an urbanised society from the rural, the resultant ecology of our world, whilst attempting to reassess land art and its relationship to Arte Povera and its legacy. The process is just beginning but these are the paths I am navigating.

• If you could go back 10-20 years in your art career what would you tell your younger self?

Never reach what you perceive to be the summit, but always imagine you will.

• If you could go forward 10+ years, what do you hope to have done or not done?

Eluded the summit.

Solo exhibitions and projects include

The Asset Strippers, Tate Britain Commission, London (2019); L’Atteso, Officine Grandi Riparazioni (OGR), Turin (2018); Cloak of rags (Tale of a dismembered bank, rendered in blue), Galleria Franco Noero, Turin (2017); tools that see (possessions of a thief) 1985-2005, neugerriemschneider, Berlin (2016); Cloak, Noveau Musee National de Monaco, Monaco (2016); Imperfect geometry for a concrete quarry, Kalkbrottet, Limhamn, Malmö, Sweden (2016); Amnesiac Shrine or The Misplacement... Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam (2016); Gang of Seven, 303 Gallery, New York (2015); Studio apparatus for Kunsthalle Münster, Kunsthalle Münster (2014); Eighty Circles through Canada, Tramway, Glasgow (2014); Amnesiac Hide, The Powerplant, Toronto (2014) Mike Nelson, Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver (2013); More things (To the memory of Honoré de Balzac), Matt’s Gallery, London (2013); M6, Eastside Projects, Birmingham, UK (2013); space that saw (platform for a performance in two parts) neugerriemschneider, Berlin (2012); 408 tons of imperfect geometry, Malmö Konsthall, Malmö, Sweden (2012); I, IMPOSTOR, British Pavilion, 54th Biennale di Venezia (2011); Quiver of Arrows, 303 Gallery, New York (2010); A Psychic Vacuum, Creative Time, New York (2007); AMNESIAC SHRINE or Double coop displacement, Matt's Gallery, London (2006); Triple Bluff Canyon, Modern Art Oxford (2004); Nothing is True. Everything is Permitted. ICA, London (2001); The Deliverance and The Patience, a PEER Commission for the Venice Biennale (2001) and The Coral Reef, Matt’s Gallery, London (2000).

Group shows include 13th Gwangju Biennale (2021); MaytoDay, Gwangju (2020); 12th Gwangju Biennale (2018); 250th Summer Exhibition, Royal Academy of Arts, London (2018); Wanderlust, the High Line, New York (2016); La Vie Moderne, 13th Biennale de Lyon (2015); INSIDE, Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2014); September 11, MoMA PS1, New York (2011); Singapore Biennale (2011); Altermodern, Tate Britain (2009); Psycho Buildings, Hayward Gallery, London (2008); Eclipse: Art in a Dark Age, Moderna Museet, Stockholm Sweden (2008); Reality Check, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, Denmark (2008); Turner Prize, Tate Liverpool (2007); Frieze Projects, Frieze Art Fair, London (2006); and Turner Prize, Tate Britain, London (2001).

Mike Nelson is represented by 303 Gallery, New York; Galleria Franco Noero, Turin; Matt's Gallery, London; and neugerriemschneider, Berlin.