Doug Fishbone

https://www.dougfishbone.com/en/home

Instagram: @dougfishbone

BIO,

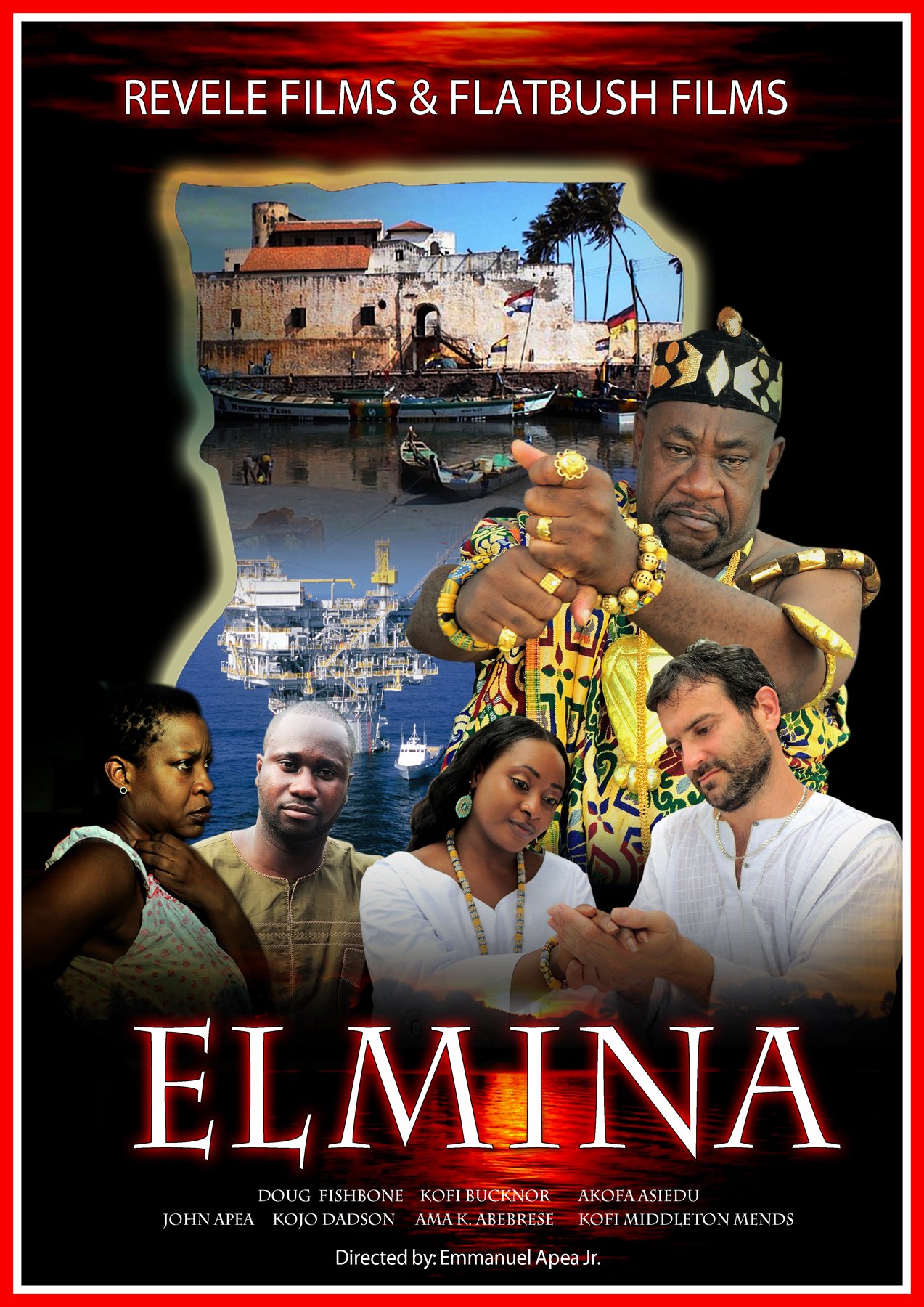

Doug Fishbone is an American artist living in London, who earned an MA in Fine Art at Goldsmiths College in 2003. His film and performance work is heavily influenced by the rhythms of stand-up comedy - leading one critic to call him a “stand-up conceptual artist” – and examines some of the more problematic aspects of contemporary life in an amusing and disarming way. His film project Elmina, made collaboratively in Ghana, had its world premiere at Tate Britain and was nominated for an African Movie Academy Award in Nigeria. He is the Course Leader of the Graduate Diploma in Fine Art at Chelsea College and is a trustee of the Yinka Shonibare Foundation in London.

1 - Could you explain your practice? Only you know why you do what you do.

I would say my artistic practice is an investigation into how we make sense out of things in the world around us, largely through playing with context and perception. I work across a range of media – performance, film, video, installation, print, and am currently working on a series of paintings – and they all rely on a similar conceptual gambit of moving things from one context to another to see what this makes possible. I sometimes think of it as plonking things where they don’t belong, to generate a kind of multivalence, something that transcends one single reading.

My first major work in the UK involved an installation of about 30,000 bananas placed in Trafalgar Square in 2004, which was inspired by something I saw in a marketplace in Ecuador and simply reframed in an unexpected context. Something entirely normal and banal, even, in one cultural framework did something quite strange and mysterious when placed where it did not belong, opening up a wide discussion – about public space, globalization and supply chains in commodity production, and the relational potential of art making - simply through being plonked somewhere unexpected.

My 2010 feature film Elmina in Ghana, in which I acted as the lead in an otherwise completely Black African production, without addressing whether my character was meant to be White or Black, did something similar by placing me where I did not logically belong, narratively speaking. This anomaly of casting was simply never addressed - a bit akin to how a singer in an opera might take on a role without needing to BE the particular identity, like an African American singer singing Madame Butterfly. I wanted to challenge ideas of role and representation in film, which can be oddly inflexible, and create something that could operate in different places under different terms depending on the context in which it was seen. How might an audience in Ghana interpret it compared to a London audience, and what kind of distribution strategies become available when one thinks outside one singular framework?

I have done numerous projects which play with this gesture in one form or another:

placing a cheap Chinese replica of an Old Master painting in the middle of the Dulwich Picture Gallery in London in 2015 to question ideas of aura and authenticity; presenting an artist-designed mini golf course at the Venice Biennale in 2015; situating an enormous model of a derelict Irish housing development – replete with its own working street lamp and corrugated on fence - in the middle of the Crawford Art Gallery in Cork, Ireland in 2021; or recreating a public monument of the notorious 13th Century anti-Semite Simon de Montfort in a gallery in Leicester in 2022.

Likewise, my performance and video work rely on taking images outside of their original context and weaving them into narrative and visual tapestries that create unexpected harmonies and dissonances.

There is an endless potential in playing at the margins. How things carry meaning, and how this can be disrupted, are a source of constant fascination to me.

2 - Is art relevant today?

At times like these, with so many dreadful geopolitical situations raging, and so much anger everywhere, it can feel like art can has little real impact on people’s lives. It can be dispiriting to see how different groups use art to co-opt and promote political agendas, and to scream at and past each other. To me this can deaden the potential of art, which is a spiritual endeavour that defies easy categorization. But as a space of reflection and meditation on our lives and the world around us, art is always relevant. I just think we need to be honest about what it can and cannot do effectively, for instance in thinking about how art and activism relate, and to maintain a distinction between the practice of art making and the wider art world.

3 – We are always asked what other artists influence us, we want to know what art you don’t like and which influences you?

There is very little I would say I dislike outright, or couldn’t see as intriguing from one angle or another, especially when you detach something from its original context. As someone who has spent many years repurposing found imagery and recontextualizing ideas, I try to embrace a kind of constructive ambiguity wherever possible. Moving beyond the intention of the artist when looking at other people’s work, if that intention can even be clearly identified, allows for endless possibilities, and I can’t really say I dislike anything fundamentally. There is a great quote to the effect that wherever you look, there is something to see. I have heard it attributed in one form or another to both the Talmud, and Dr. Seuss, which perhaps attests to its universal validity.

4- If you could go back 10-20 years what would you tell your younger self?

I came to art late in life, having come to the UK in my early 30s to do my MA at Goldsmiths after years of different knocking about. I had some weird jobs that might best have been avoided, and to be honest, I wish I had begun the journey of becoming an artist earlier. I had a terrifying art teacher when I was a schoolboy in New York who used to bellow at us and smash her desk with a hammer, or smash the overhead pipes with a broom, to get us to quiet down. She well and truly scared me off the stuff for most of my childhood, and crushed my enthusiasm, which seems a great missed opportunity. I keep this experience in the back of my mind now that I do a lot of teaching myself.

I also would push myself to be more open to failure in the work, and create much more work just for its own sake, regardless of whether there was an exhibition waiting for it, or any specific professional outcome intended. As with many types of work, the pull towards professionalization can compromise the joyfulness and playfulness that might excite one about something in the first place.

5 – If you could go forward 10-20 years what do you hope to have done or not done?

In the next 10 or 20 years, if we are not all living on rafts, or in some kind of Road Warrior-like dystopia, I hope I will have been able to open up my own art academy, which is something I have been thinking about for a number of years. I love teaching, and I feel that speaking about work with people who care about it and helping them develop their artistic voices is an immense privilege. I would like to create something independent, as it would allow for freedoms not available within the institutional teaching of art. Something that would benefit from the participation of many wonderful artists and teachers I have met over the years, for a small group of students, with a flexible and joyful approach. I think there is ample room for initiatives like this.