In this issue, we are exploring the use of textiles in contemporary art. While fabric, wool, silk, and textiles have been a wonderful source of creativity since time began, as a medium it has now taken center stage in Contemporary art with art practitioners using it to draw, make sculptures, use it for performance and create exciting works. From Emin's huge calico and wool drawings, Sheila Hicks huge sculptural installations, and Phyllida Barlow's use of fabric to challenge our ideas of space. Here we explore how fabrics and textiles are translated through our cultures and how certain textiles or textile trades are associated with separating and influencing culture, gender, and class.

Resident Writer - @Micheala Hall

Waste Not Want Not

Louise Baldwin. ‘Wednesday’, Mixed media.

With sustainability and looking after the environment becoming more and more key to our everyday lives in 2021, the materials we use to create things are under interrogation more than ever before. This is something that artists have long considered in their works, but that now for some artists is becoming the focus of their approach to making. That is, re-using and re-purposing materials to create something new with the aim of nothing going to waste.

British artist Louise Baldwin does exactly this in her works. Baldwins’ works appear soft and intricate with thread detailing and inviting textures. Baldwin’s works are made up of found materials; imagery, domestic packaging along with the fabric and stitches that complete the composition of each piece. In her piece ‘Wednesday’ the materials work together to form an intricate maze for the viewer’s eye to explore the elements that create the overall image they can see. At first, we may see the image as elements of colour and block but as we look closer, we can see all of the found imagery and stitch details emerging to change our perception of what we first thought we saw. What Baldwin manages to do in her body of work is use those materials we may not look twice at if we saw them on their own and turn them into a fantastical, colourful composition that allows the viewer’s mind to explore the idea of the material itself.

Louise Baldwin, ‘Imperial Quilt’, 2012, mixed media.

Another artist who explores materiality as a key focus in her work is British artist Susan Stockwell. Similar to Baldwin, Stockwell re-purposes found materials. What Stockwell does fantastically is to use these materials in such a way that we see a relationship of their purpose to something of political or social significance. In her piece ‘Imperial quilt’ (2012) Stockwell plays on the idea of the material we associate with a quilt and instead creates a hand-stitched patch quilt made up of recycled maps of the world. Compositionally, the world order as we know is messed up in the quilt with the Middle East at the centre and other countries surrounding it. However, there is a part of America in most patches of the quilt and this symbolises the power and influence of America on the world stage politically. This again, similar to Baldwin’s work, really encourages the viewer to focus on the physical material of the piece itself and what the material is trying to tell us.

What both artists achieve with their re-use of found and existing materials is the creation of a new composition that invites the viewer to explore a new idea of the physicality of material and the context of its use. This goes hand in hand with the artworks having some influence on sustainability and the idea of not wasting a single thing. After looking at Baldwin and Stockwell’s works, it becomes clear that the discarded piece of fabric or image we perhaps walked past in the street could gain a whole new identity in which the material is revitalised and more interesting than it may initially seem. What stands out most from both of these artist’s work is the opportunity of materials and using what we can find. This points to the bigger opportunity that is facing us all worldwide, the opportunity to reduce waste, be precious with what we have, live more sustainably, and think of creativity with a new approach- to what is possible when we use our imagination.

**********************

Artist - Kim Thornton

Contact - https://www.instagram.com/kimthornt/

Bio - Kim Thornton’s practice combines making and photography with humour to disrupt stereotypes and to create surprise narratives. Using domestic materials she fashions costumes and transforms objects and uses them to stage unexpected scenes. The scenes are darkly playful responses to traditional daily life, drawing on memories, anecdotes, observations, and experiences to explore everyday tasks. Through the study of domesticity and gender Thornton’s work plays with behavioural expectations and subverts everyday tasks to suggest a secret life of make-believe and fantasy.

“Humour is not resigned: it is rebellious.”

Sigmund Freud, 1927

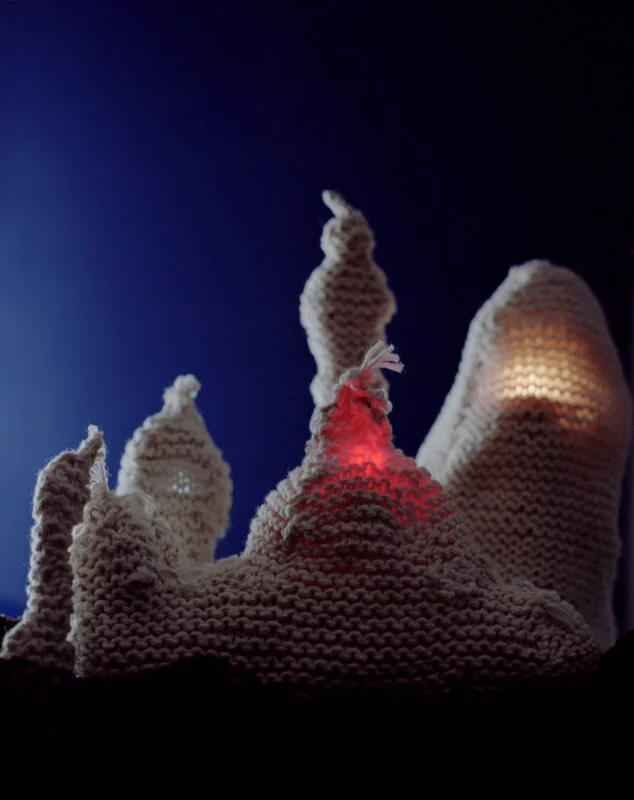

Knitty City (Indigo), 2006

Ideas come to me in many ways, through personal experiences, observations, an art reference, or a news story for example. The challenge is always how to respond so the message is clear but delivered with the humour that is a staple of my practice. Humour is a great tool for illustrating the ridiculousness of something or illuminating unwelcome behaviour without being too didactic. I also happen to love humour!

The process often starts with the thought ‘wouldn’t it be funny if…’ and I then begin to translate this into a crafted object or costume using domestic materials. Although I employ various textile skills in my practice I thought it would be interesting to explore the way I have used knitting in my work, particularly as over the past 18 months many people have turned to knitting as an occupation to see them through the difficult pandemic months, using it to calm themselves, to comfort and to connect with others, at least virtually (Olympic diver Tom Daley is a famous example).

My technique is home-baked and organic and often involves laying my knitting against a pattern made from drawing around myself or from an object or clothing item, increasing or decreasing stitches as I go until the shape I am aiming for appears. The materials I choose are usually domestic and include mops, dishcloth cotton, and J-cloths, and I only really know one stitch!

Dishcloth cotton connects me with my grandmother who for as long as I can remember knitted all the cleaning cloths she used. It was the material I chose to make my first textile sculpture Knitty City in 2006 when I knitted scaled versions of five iconic London buildings – the Gherkin, St Paul’s Cathedral, Nelson’s Column, Big Ben, and the BT Tower. I had been reading an article by psychologist Ros Minsky on the containment of women and wanted to find a way to combine domesticity with the workplace at these traditional bastions of male power by containing them in soft knitted exteriors – it seemed such a funny idea at the time but of course, the serious message is always at the heart of my making. I was thinking about what happens when more women enter these professions, the need to accommodate home and work commitments, and how it impacts the work environment and men. These softened buildings were arranged into a landscape and photographed to reflect different times of the day.

The Long Silence: Mansplaining, 2019

Another dishcloth cotton project was to knit a corset, cap, and matching fan for The Long Silence, a project looking at how women have been culturally primed for public silence. In the three images of the series, a woman is wearing a constraining item of clothing, the corset, made from dishcloth cotton, J-cloths or dusters. She holds up matching fans on which the protest words Manologue, Mansplaining, and Manterruption are embroidered. The work was a response to feeling particularly exasperated following yet another experience of being silenced and was informed by the secret fan language developed by women during the eighteenth century to transcend the prevailing etiquette and to facilitate silent communication. In Mansplaining my knitted corset has a Jean-Paul Gaultier, inspired cone bra and the fan is worked on a collection of meat skewers. The embroidered text is my silent form of communication. In a film also titled The Long Silence, wearing the same costumes, I attempt to imitate traditional dance moves from burlesque, flamenco and Japanese fan dancing and to incorporate some of the Victorian fan languages.

The Smile on her Face, 2012

The Smile on her Face was inspired by the collection of writing exploring the objects of everyday life in The Gendered Object, ed. Pat Kirkham. In Jane Graves’ essay The washing machine: ‘Mother’s not herself today’ society’s vision of the washing machine being designed to stand in for the mother is examined, how it continues to work even when she is not there, how it is the smile on her face. However I find my washing machine can be demanding; rather than existing quietly in the corner of the room it is constantly beeping and flashing at me for attention. My miniature knitted appliance makes a constant noise, powered by vibrators, and it too has a flashing light.

Home Entertainment: La Toilette, 2018

Pulling the wool out of cotton mops and knotting it together to create a ball of yarn makes another great knitting material. In 2018 for an exhibition in Oxford I created Home Entertainment, a series of large-scale photographs. The works show a costumed woman playing alone at home re-enacting childhood memories such as rowing the upturned kitchen table and driving a pretend car sitting on a saucepan. In La Toilette the woman is playing with make up under a homemade tent wearing a top and skirt knitted from mops, with a styled mop wig on her head. The title of the work comes from the history of painting from which women were largely excluded unless they were being observed carrying out their ablutions!

Last year during a break in the pandemic I was lucky enough to escape to the coast for a week where the sky and sea were uncharacteristically clear and a stunning blue. Packing for the trip with Covid restrictions reminded me of past holidays with young children when I had tried to take everything I could possibly need for the week’s ‘rest’. However, this J-cloth knitted swimsuit in Lady in Blue on the Beach reflects the domestic duties that continue no matter where you are. I cut the J-cloth into strips, tied them together, and drew around one of my swimsuits to make the pattern. It also reminded me of the knitted swimsuit I wore as a young child with its water-retaining properties and the inevitable cold, soggy discomfort. For the photo it was a beautiful day, the calm of the sea complements the comforting action of knitting on the beach and connects me with the landscape whose blue perfectly matched my costume. In true British fashion, the few other swimmers on the beach politely ignored me but I hope it brightened their day.

Lady in Blue on the Beach, 2020

*********************

Artist - Victoria Duffield-Harding

Instagram - kikki.harding

Bio - I am a mature art student, still learning and striving to share my art. I have two children and live in Warwickshire. My work is primarily about experimenting with different media and materials, I'm learning how to write about art!

The May Morris Problem

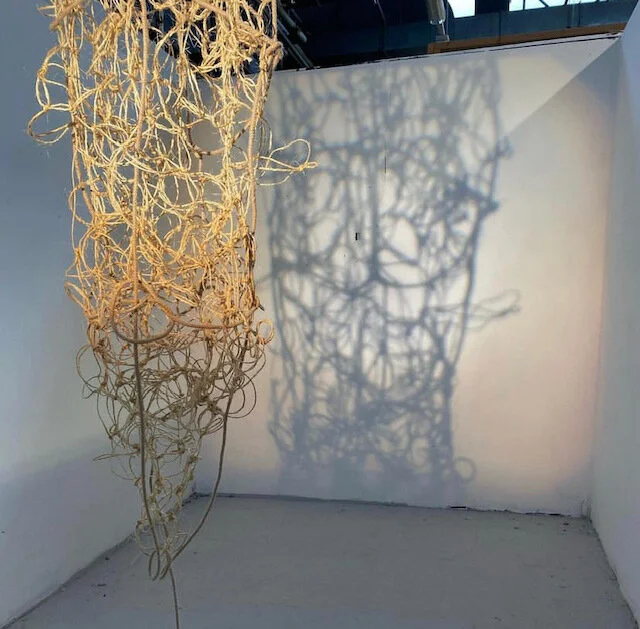

Body of Knots by Victoria Duffield- Harding

A form made from knotted rope and string with a light shining through it to reveal its shadow on the walls.

My introductions to textiles were as a hobby, a craft, or an industry. Early education led me to firmly believe textiles, particularly sewing was “for girls”. On-field trips we visited places such as textile mill museums, where we were shown the cottage industry, described as being run by women. Carding and spinning in their hovels producing yarn to the growing textile factories. We were shown how this craft became a large industry, with the introduction of the spinning jenny and we were told how children lost fingers in the looms and many spinners were suddenly unemployed. One of the most troubling images I have of the textile industry is the image of May Morris, the incredibly skilled embroiderer and textile designer who lived for 50 years in her father's shadow. William Morris himself owned his own arsenic mine to make his famous green dyes, a compound of copper and arsenic named Scheele's Green. Reportedly he denied it even though it seemed to be common knowledge that the wallpapers were making employees and customers sick. This seemed like a massive contradiction to the image he tried to project as the socialist arts and crafts artisan. For me, turning May into the personification of Victorian restraint and a symbol of exploitation. My May Morris problem persists today, we are now told that “20% of all industrial pollution comes from the textile manufacturing process and globally 80% of garment workers are women”. (sources weforum.org/ labourbehindthelabel.org)

At school, I was pretty good at art and crafting, home economics, history, and English. I loved English. We had to take home economics then, only the girls. The school careers advisors later told me my best bet for the future was to become a housewife because I was good at home economics. I was furious, I didn’t choose to do home economics, I was just as good at the other subjects! What kind of job is a housewife anyway?? At this point, I became discouraged to take up any craft involving textiles or cooking for the fear of being typecast ‘a housewife in training’. My current artwork absolutely reflects this experience, I have become very interested in fabrics and their contextual language, particularly as an extension of the body.

I have experimented with white sheets, latex ‘skins’, and ropes and string. Rejecting the idea of weaving but using knotting as an undone, deconstructed process and resisting making work the way a woman should make’ (make pretty). Certainly, this is my protest, my way of discussing the theme of restriction, concealment, and censorship, and the memories we carry for places or leave in places.

I consider the only way to practice with materials is to do just that – experiment and practice forming them and deconstructing them. Each material carries its own process with associated concepts which may be personal and universally understood also. In this way, the language emerges, through this conversation and experimentation with the material itself.

“I always had the fear of being separated and abandoned. The sewing is my attempt to keep things together and make things whole.”- Louise Bourgeoise. (source hauserwirth.com)

I started noticing artists using fabrics in interesting ways, in ways which I would not describe as a craft. The use of these works was different. Eva Hesse, Louise Bourgeois, Heidi Bucher, and Christo and Jeanne-Claude. I saw sewing as healing, a kind of soft Kintsugi, the metaphorical act of stitching ourselves back together. I felt this language was easily understandable and addressed life trauma – both for the maker and the viewer. I saw sewing and fabrics as a newly discovered language of abstract concepts, I saw the political significance of the wrapping and unwrapping of the Reichstag in Berlin (1995). (source christojeanneclaude.net) The power the simple fabric had that day when the building was unveiled was a simple and universally understood gesture yet highly symbolic and therefore of huge cathartic meaning to the country.

I see artists discussing home and memories, Heidi Bucher’s huge latex “Hautraum” documenting human experience and collaboration with spaces such as homes. (1985-1988) (source heidibucher.com) Made from silk, Do Ho Suh monumentalises spaces such as homes with amazing detail. Staircase (2010). (source tate.org) His work directly references the relationship between silk and the home.

Far from being only a craft in art, I see a rich history of craft informing new ways of seeing ourselves through our intimate relationship with textiles. I see artists experimenting with fabric to express unique voices in exciting ways. Thankfully textiles don’t just mean sewing.

Victoria Duffield-Harding

***********

Artist - Gill Crawshaw

Instagram - @gillcrawshaw

Bio - I am a curator and draw on my experience of disability activism to organise art exhibitions and events which highlight issues affecting disabled people. Exhibitions have addressed the representation of disabled artists (Possible All Along, 2020), charity (Piss on Pity, 2019), cuts to welfare and public spending (Shoddy, 2016), and access (The Reality of Small Differences, 2014).

I am interested in the intersection of disabled people’s lives with textile heritage in the north of England, as well as contemporary textile arts. I have a degree in Textile Design. I gained an MA in Curation Practices from Leeds Arts University in 2018. I’m one of the founders of DISrupt, a new collective of disabled artists in Leeds.

The power of textiles for disabled artists

Textiles have been part of disabled people’s lives for many years. So it is perhaps not surprising that they are currently a burgeoning art form amongst disabled artists.

I’m a disabled curator, my practice is informed by my past experience of activism within the disabled people’s movement. I’m also interested in the intersection of textiles and disabled people’s lives - contemporary textile art and disabled artists who use these media, as well as disabled people’s roles in textile history. With a degree in textile design many years ago, I find myself regularly drawn to textiles, and I’ve noticed that many disabled artists are too, especially women. Many of them, like me, are based in the north of England, reflecting the historic centre of the UK’s textile industries.

The idea of subverting textile materials and methods has particular resonance for disabled artists when we think of disabled people’s history of containment and segregation in various institutions over the centuries. Needlework has regularly been used to keep disabled people quiet and busy, whether in Victorian asylums and workhouses or in day centres and occupational therapy wards of the 20th century (and beyond).

There were several reasons why textiles and needlework, including embroidery, dressmaking, knitting, and basket weaving, were permitted activities in institutions for disabled people. They were introduced to stave off boredom for disabled workhouse inmates who couldn’t do hard labour, or as part of the rehabilitation of disabled ex-servicemen. They were a way of fundraising for institutions and gave disabled school students training for employment.

Needlework was thought to be calming and this idea of textiles, and indeed other art forms, as being therapeutic for disabled people is difficult to shake off for contemporary disabled artists. Rather than being recognised as serious artists, disabled artists, particularly those using textiles, are often presumed to be making work for their wellbeing, or as a hobby. Their art is considered to be therapy rather than a professional artistic practice.

I am currently writing about the connections across the decades between the remarkable embroideries produced in asylums by Mary Frances Heaton and Lorina Bulwer, and the work of contemporary disabled women artists. They have all found a voice through textiles and used the art form to share narratives about the reality of their lives. My essay will be published later this year in Disability Arts Online.

I’ve organised two exhibitions in Leeds that were of textile work by disabled artists, The Reality of Small Differences in 2014 and Shoddy two years later. I’ve mentioned both before on this website (Issue 10: Activism https://www.haus-a-rest.com/issue-10-opinion-activism) because they were conceived as a form of protest, or to make a political point. Far from being restrictive or conventional, the open calls for both exhibitions brought in exciting, experimental and challenging work which included repurposed textile items, sound art, installations, and conceptual pieces. Artists also used traditional needlework techniques, paired with unusual materials or depicting unexpected subjects, including subjects relating to disabled people’s lives and experiences.

The publication about Shoddy gives a taste of the work: https://issuu.com/gillcrawshaw/docs/shoddy_booklet_aug_2016

Even when my projects are not textile-focused, invariably some pieces of textile art will feature, for example, Alabama thirteen, Ria and Judit Mathe’s work in the online exhibition Possible All Along (2020): https://possibleallalong.co.uk/

Disabled artists are using textiles to tell personal stories and share their feelings and viewpoints. Textile artist Hayley Mills-Styles (https://hayleymillsstyles.com/) creates hyper-real machine embroideries that act as an archive of memories, or that catalogue her feelings around depression and anxiety.

Raisa Kabir (https://lids-sewn-shut.typepad.com/) is an interdisciplinary artist and weaver, concerned with the cultural politics of cloth. She encompasses personal experience and expands the narrative to address wider issues of colonialism and labour. She uses her body in (un)weaving performances which she describes as a ‘comment on power, production, disability and the queer brown body as a living archive of collective trauma’.

Faye Waple (https://instagram.com/fayewaple) also uses her body, and brain, as her subject, while keeping emotional distance through the use of abstraction. The wisps and lines in her series of embroidered panels titled Reductivism (2014) turn out to detail from her MRI scans.

Other artists use textiles to reveal uncomfortable truths. Using soft textile materials can convey a powerful message stealthily yet effectively. Sandra Wyman (http://thedyershand.blogspot.com/2014/02/connection-at-forge-mill-needle-museum.html?m=1) presents us with the reality of domestic abuse, through the medium of a quilt. On closer inspection, the quilt is covered with stitched text telling of her mother’s and her own experiences. These are a sharp contrast to the usual associations of safety and security that a quilt calls to mind.

Feminist themes are common in disabled women artists’ work. Judit Wilson (https://outsidein.org.uk/galleries/judit-wilson/) is concerned with the long-term, generational effects of women’s oppression. She ultimately celebrates women’s strength with her surreal juxtapositions of found objects and toys bound with wrapped thread. Katya Robin’s (https://katyarobinstudio.co.uk/) silk headscarves, Coin Icon, are also celebratory, reminding us of the touch of luxury and flash of colour that these affordable accessories provided to working-class women.

Disabled artists are rejecting the constraints of needlework that were imposed in institutions and overturning stereotypes of disabled people as passive and dependent. Instead, they are using textiles to claim their space as artists, to be powerful, and to protest.

**************

Artist - Samuel Nnorom

Instagram - nnoromsamuel

Ikenga

Conceptually, the use of African wax fabric known as Ankara fabric in my work draws its concept from the vacillating history of Ankara fabric to Africa, and the use of bubble techniques through the process of rolling, tying, stitching, sewing, and installation becomes a metaphor to conceal and unconcealed the temporalities, luminaries and the uncertainties of human behaviors and activities.

However, this piece titled: Ikenga is an excerpt from a body of work themed: "Ututu" which literally connotes morning or awoken. Ikenga (Igbo literal meaning "strength of movement") is originally a horned Alusi found among the Igbo people in southeastern Nigeria. It is one of the most powerful symbols of the Igbo people and the most common cultural artifact. Ikenga is mostly maintained, kept, or owned by men and occasionally by women of high reputation and integrity in society. It comprises someone's Chi (personal god), his Ndichie (ancestors), aka Ikenga (right hand), ike (power) as well as spiritual activation through prayer and sacrifice. Ikenga is a personal embodiment of human endeavor, achievement, success, and victory. It also governs over the industry, farming, and blacksmithing, and is celebrated every year with an annual Ikenga festival. It is believed by its owners to bring wealth and fortune as well as protection. However, my re-invention of this piece is to coin out the identity of African culture in the global space which I represented as an astronaut's head. Personally, this piece evokes the meager history of black culture and challenge the rewriting of history, contributions, achievements, powers and the economic strength of black in the contemporary societies.

In an attempt to lend my visual voice, I found this piece interesting and challenging to depict my culture in a contemporary setting where my materiality is scarcely understood by people. I hope that this piece becomes part of black contemporary cultural history and its renaissance in the modern world.